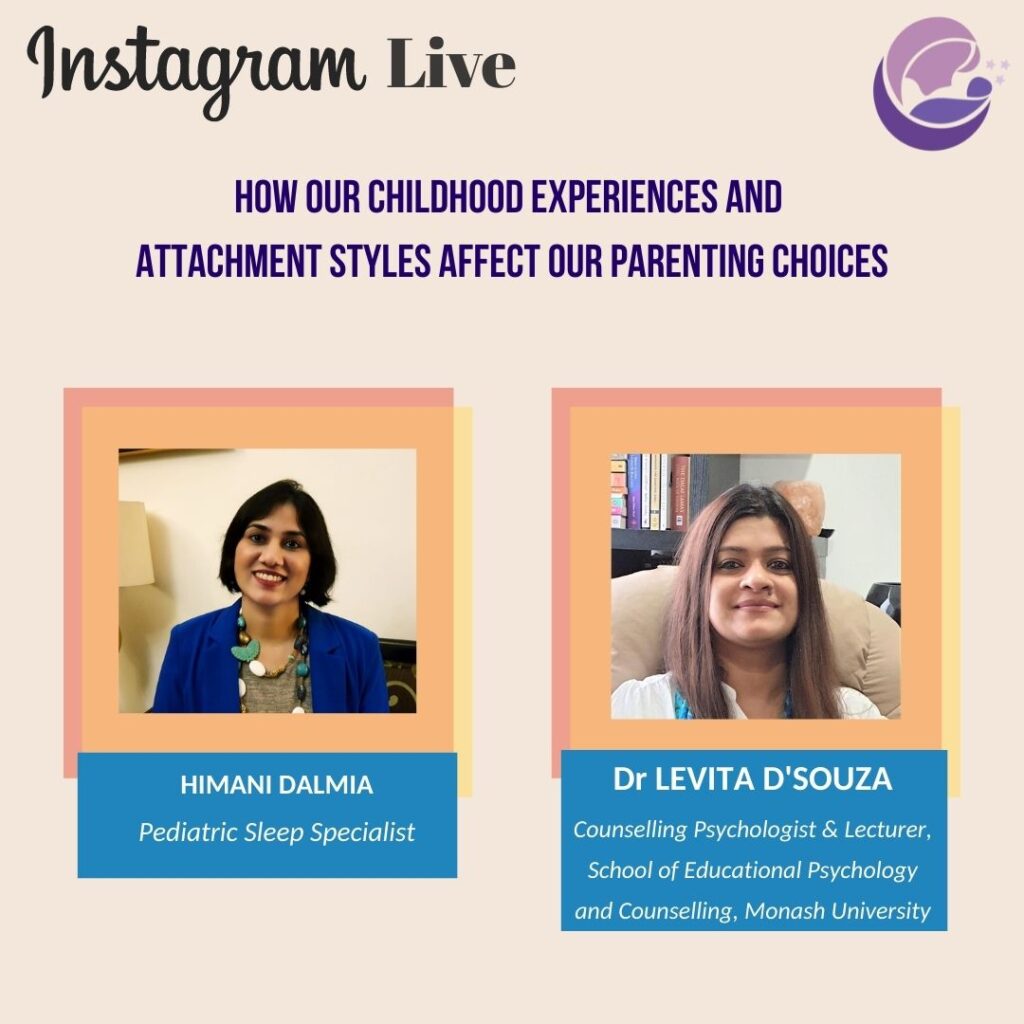

Instagram Live with Dr. Levita D’Souza

Instagram Live with Dr. Levita D’souza I had a riveting conversation with Counselling Psychologist and Researcher, Dr Levita D’Souza, on Instagram Live, where we talked about attachment theory, attachment styles, how our own childhood experiences affect our parenting choices, ruptures and repairs in the bonding process with our babies and children, how parentj g is an opportunity for personal growth and much more! Unfortunately, there were some disturbances in the audio. So that Levita’s amazing insights don’t get lost, I am sharing a transcript for the conversation here. Do read through until the very end so that you don’t miss some transformative truth bombs! How our childhood experiences and attachment styles affect our parenting choices. Himani: Hi everyone. Thank you for joining in for this live with Levita D’Souza. I’m super excited because every conversation I have with Levita is just full of these truth bombs that she tends to drop. Levita is a Registered Counseling Psychologist and Lecturer within the Faculty of Education at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia. Her research interests are in the area of perinatal psychology, adverse childhood experiences and its impact on attachment patterns and subsequent parenting practices. Within this space, her current research projects are looking at psychological factors affecting first-time fathers as they transition to fatherhood and father-child bonding. She’s also undertaking research on cultural influences on parenting choices in relation to infant sleep. So that’s really where Levita and I have had many conversations – where infant sleep is concerned. And, as an Indian living in a sort of industrialized, westernized – “westernized”, not “Western” – country, I’m sure you’ve faced this dichotomy and perhaps that was one of the factors that drew you towards this research. So, could you tell us a little bit about your journey and what drew you to your current work? Levita: Yes, I think my journey first started with my quest and questioning around mental illness. Why people are mentally ill; if it runs in families, does it mean I’m doomed; does it mean that we cannot do things differently. And that led to my early work in my early study working with families where there has been mental illness. And what I found was that some outcomes were much better than others. So, for some patients, the outcomes were much better than others. And the same sort of thing was replicated when I was working with children who had experienced trauma. You know, crap happens to everyone. But some children were better able to deal with the trauma and overcome it or manage their symptoms compared to others. And what I could see clearly was those early sorts of parenting experiences. And it wasn’t till I became a mum myself and I started to question why – who am I as a mother? What kind of a mother do I want to be? What from my own parenting experiences do I want to bring into how I parent my child? What do I not want? – that I started to really dabble in this thing of attachment theory and how that can influence – those really early experiences can influence – later outcomes for children. And so then I’ve landed in this space where, very crudely, I say “how not to be a jerk of a parent”. That’s what the transition to parenthood is. What influences us, what will help us be better parents? What do we draw on? What do we not draw on? What do we want to leave behind? And attachment, I think plays a big role in that. Himani: So, you know, just for some of us and the uninitiated and the layperson, the lay parent rather, could you very simply explain attachment theory – what you spend years teaching your students – in about two minutes? (laughter) Levita: I’ll try. I will try. I was reflecting on this and going, “can I reliably do it?” But I’m going to try this. So, very simply… Himani: You can take ten minutes. I’m joking about the two minutes. Levita: Thank you! Much appreciated (laughter). So, very simply, it’s like a bond. It’s a bond that exists between the baby and the caregiver. For the purpose of this talk, I will interchange between “caregiver” and “mother” but I want to absolutely acknowledge that families come in all forms and so it can be the father, it can be the grandmother, or any caregiver who is consistent, who is reliable, who is dependable, who is sensitive, and who is able to attune to the baby in a timely sort of way. And so, what is attachment? It’s a bond between the baby and the caregiver. Why does it exist? It exists purely and solely for the purpose of survival. So, when the baby is born, the baby is born with a system, what we call a “bio-behavioural system”, which it uses to cue the parent that they need things, to meet their needs. So, let’s take an example, here’s a little baby. They experience hunger, and they experience hunger on a very physiological level, right, it’s a biological behaviour. That hunger puts the baby’s system in chaos. It experiences pain. The baby doesn’t immediately cry. What the baby might do earlier to cue the parent would be root, stick their tongue out, put their hand to their mouth, and these are, sort of, very early signs where the baby is cuing in the caregiver to say, “Mamma, look at me, I have a need, I’m expressing this, attune to me, meet my need, make me feel good.” When the baby does that, the mother goes, “oh, you’re hungry! You want me to pick you up, let me feed you.” When the mother meets that need, the baby’s system – that had started to be in chaos because of the hunger – returns to this really calm, nice, happy place. Mum feels good because baby has stopped crying; baby feels good because baby’s needs

We Need to Talk About Encanto

We Need to Talk About Encanto With its latest animated extravaganza, Encanto, Disney weaves its magic to shine a light on inter-generational trauma. (Contains spoilers) The latest offering from Walt Disney Animation Studios, Encanto (streaming on Hotstar in India), is a rapturously imagined, gorgeously rendered musical about the fissures within an extraordinarily gifted family. Capturing tiny hearts with its rainbow-lush imagery and catchy, chart-topping soundtrack (songs by Lin-Manuel Miranda of Moana and Hamilton fame), Encanto has also taken over social media with its themes of intergenerational trauma, sibling rivalry and immigrant displacement. Encanto-themed content on TikTok has gone viral and parenting influencers on Instagram have dived deep into the intergenerational trauma so poignantly evoked by the movie. Every social media platform is brimming with posts and comments by users talking about how the movie reduced them to tears, how they related with such-and-such character, and how the soul-stirring, cathartic music plays on repeat in their homes (it certainly does in ours!) Encanto is the story of the Madrigal family – matriarch Abuela Alma Madrigal, her children and grandchildren – all of whom live in a magical home in a misty Colombian rainforest valley. The Casa Madrigal is a worthy 21st century addition to the lineage of Disney castles, with its ornate tiles, vibrant color palette and enchanted doors and windows (also floors, staircases, furniture and crockery!). And yet, Encanto abandons European fairy magic for the largely Latin American literary tradition of magical realism (think Isabel Allende’s House of Spirits, Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude). The dark backstory of the movie involves Abuela and her husband, Pedro, fleeing political violence shortly after the birth of their triplet babies. Abuelo Pedro martyrs himself in order to save his family and his people, leaving Abuela and the babies alone and adrift. In their “darkest moment”, Abuela recounts, they were granted a miracle: a magical, ever-flaming candle that is the source of their power, an enchanted home to replace the one they have lost, and powerful mountains that rise up to protect their little village. But that’s not all. Every member of the Madrigal family, starting from the triplets and passing onto their descendants, is given a magical power, a “gift” that is bestowed on them when they open their very own door in the enchanted house, a gift that allows them to serve their community. All, that is, except the heroine of our story, Mirabel. She is the only member of the special family who returns empty-handed from her “door-opening ceremony”. Mirabel’s mother, Julieta, can cure the ill with food. Her aunt, Pepa, can change the weather with her mood. Her sister, Luisa, is strong like Hercules and can lift mountains or churches; her other sister Isabella can grow flowers and is perfect in every way. A cousin can shape shift, another can talk to animals, another has superhuman hearing powers and an uncle can tell the future. Every member of the Madrigal family, except Mirabel, has a superhuman gift, like Cousin Dolores, who can hear a pin drop. These superpowers allow the Madrigal family to serve their community. As Abuela says in the opening song of the film: “We swear to always Help those around us And earn the miracle, That somehow found us The town keeps growing, The world keeps turning, But work and dedication will keep the miracle burning And each new generation must keep the miracle burning” However, all is not well in the fairy tale world of the Madrigals. Mirabel is the first to notice that the magic is fading. There are cracks in the floors and walls of the house. Her family members are losing their powers. And everyone else seems to be in denial about it! Most notably Abuela, who in fact blames Mirabel for doing “something” that is affecting the magic. Mirabel then takes it upon herself to save their miracle and thus begins the movie’s quest narrative, except, instead of journeying into strange and dangerous lands, our hero dives deeper into family history and uncovers raw wounds. Eventually, Mirabel discovers the trauma that Abuela still carries within her, that permeates all her relationships and the hearts of all her gifted family members. To save the magic, Mirabel needs to heal the wounds that fester within her family. The vision her fortune-telling uncle shows her gives her a clue: she needs to embrace her sister, Isabella, whom she has a fraught relationship with. The family needs to see each other for who each person truly is and not assign their worth to the service their “gift” can perform. At the end of the day, this is a Disney film. Abuela sees the light and redeems herself, the family and their neighbours rebuild Casa Madrigal together, the family members’ gifts and the house’s magic are restored and everyone lives happily, magically – albeit a little messily – ever after. But even in this happy ending, there is truth. Intergenerational trauma can end if one generation “breaks the cycle”. Mirabel stands up to Abuela and says: “Luisa will never be strong enough. Isabella will never be perfect enough. You’re the one breaking our home… the miracle is dying because of you.” After visiting the scene of her trauma and understanding the root of the issue, Abuela realizes, “I was so afraid of losing it, that I lost sight of who our miracle was for.” And with that confrontation, the cycle is broken. One of the reasons this movie has resonated so deeply with immigrants – and particularly Latinx immigrants – is that inter-generational trauma is pervasive where there is a history of political violence and/or displacement. But inter-generational trauma can affect other families too, families that may not have suffered through terrible historic events, but milder forms of abuse or painful family experiences. The way inter-generational trauma works is that each generation, starting from Ancestor X (usually 3 or max 4 generations above us), is unable to escape the pain of their own